This year, we are implementing a task-supported syllabus in the academy where I work. It has been a while in the making, with the plans for this being drawn up last academic year – in fact, my assignments for the NILE MA Trainer Development module were centred on it. I thought I would slowly write some reflective posts from the management perspective, beginning with an overview of the change, and why we decided to do something like this.

A quick overview of the ‘change’

Without going into too much detail, this is a two-year plan/project, with two implementation phases – we are currently in the first. In essence, I have designed a set of task sequences, which sounds fancy but really means lessons. In each task sequence, there are three lessons, and in each lesson there is a task (sometimes multiple tasks); however, the first lesson is a less complex version of the task, the second a more complex version, and then the third lesson contains a full-blown, ‘difficult’ and complex version of the task. For those familiar with task-based methodologies and syllabi, you’ll see that I decided on the target tasks (i.e., the tasks learners need to be able to do), and then the pedagogic tasks (i.e., simpler versions of the target tasks that learners progress through). The target tasks in these task sequences take place in lesson 3, while the pedagogic tasks take place in lessons 1 and 2.

How are tasks implemented?

Before we explore how the tasks will be implemented, let’s explore how our level system works. In our academy, we have 14 levels, all linked to the CEFR. I know that there is some criticism regarding linking learners and learning to the CEFR, but personally I find it a useful benchmark, especially when speaking to leaners about progress, and showing parents where their child ‘is’ in their English learning journey. Levels 1 – 6 are our Young Learner classes, and then Levels 7 – 14 are our teens. Levels 7 and 8 are our A2 courses, 9 and 10 our B1 courses, 11 and 12 our B2 courses, and 13 and 14 our C1 courses.

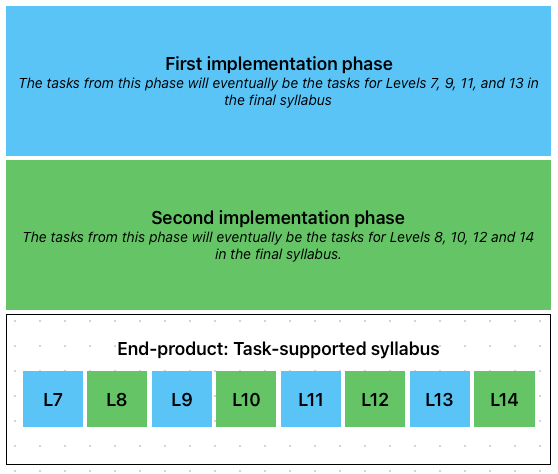

Now, that we’ve explored how the learners are organised, let’s think about the tasks. For the two-year implementation, I have group levels into pairs – so, our A2 level courses (Levels 7 and 8) will be one pair, B1 level courses another pair. There is a reason for this, which is more pragmatic then anything – but we will get to that shortly. Each of the pairs will work with a certain task sequence for one term. For example, in Term 1 this academic year, our Level 7s and 8s (the A2 pair), completed a Lego two-way instruction-giving and building task sequence, while Levels 9 and 10 (B1 pair) completed a task sequence that focused on mediating communication, with a focus on technology (I’ll get to some examples soon, don’t worry). Next term, the same process will occur although with different tasks. The reasons for doing it this way, and not having a separate task for each level is three-fold: time, feedback and end-product.

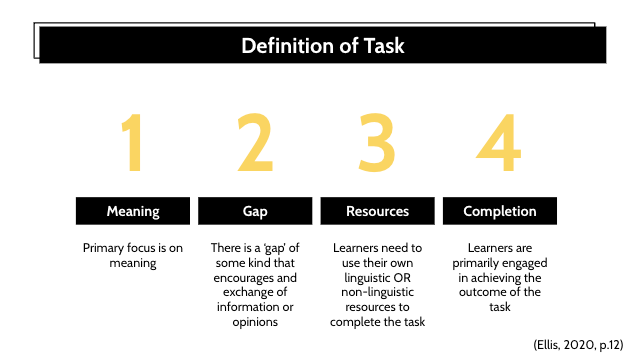

- Time: It takes me a long time to work out how to put the task sequences together. I am not following Long’s (2015) version of TBLT which requires an in-depth needs analysis and works with ‘real-world’ needs; however, I am identifying tasks that are interesting to learners, connect to some kind of real-world situation (e.g., giving instructions to someone) and follow Ellis et al.’s (2020) definition of a task (see below). Now, if I had to create a separate task sequence (three lessons in each) for all the levels from L7 – L14, it would be almost impossible time-wise.

- Feedback: By having the task sequences made and then implemented in this way, it allows me to test the tasks, then get feedback from teachers. Why? Well, I need to see how tasks are implemented and what the reactions are of learners – did the task go according to plan? Was it too simple (and I’ll talk about complexity a little later)? What opportunities to engage in Focus-on-Form did teachers have? Were the tasks enjoyable? All these sorts of questions I need answered, and if I had a task for every level, it would mean I’d need to collect far too much feedback.

- End-product: One the implementation cycle has been completed, the idea is that all levels will have different task sequences. So, the end-product is a task-supported syllabus in which Level 7 will have it’s own task sequences for Terms 1, 2 and 3. And then when those learners progress to Level 8, they will have three new task sequences to engage with (there will be no cross over). So, by creating tasks in this way, I can create the first cycle’s tasks, get feedback on these as we go along. Then, after the first year, we then focus on the second cycle’s tasks. After receiving feedback on all the tasks from both cycles, I will then be able to implement a different task sequence for each term for each level in the fully-fledged, ready-to-go task-supported syllabus. This is actually a little difficult to explain in written format, so I’ve created a visual representation of the process (see below).

Of course, we need to remember that this is a task-supported syllabus, so it runs alongside other things teachers use (e.g., course books, running Cambridge exams, etc.). This term, we ran the task sequences across the term, with lessons spread out. For Term 2 we are going to have the lessons one after the other to see if there is a better result and task outcomes.

Can we see an example?

Of course! Below the is the task-sequence for Levels 7 and 8.

There are a few things I’d like to talk about before moving on.

- Complexity: Complexity is actually one of the most difficult things to I’ve had to ‘plan’. In the task sequence above, you can see that things start fairly simple with learners being able to see each other, and then that visual support is eventually taken away. This is how complexity is increased in this task. There are other tasks for other levels that require learners to read and label a diagram (this was Level 11 and 12 for Term 1), and complexity increased here is a number of different ways – text length, number of ‘items’ to label, and the first text had the words highlighted, but the second and third texts did not. Complexity is definitely something that I’m still getting the hang of, but that’s why we have this plan-teach-feedback-adjust process.

- Assessment: You will see that in the third lesson of the task sequence, there is a task assessment. I wanted to include this so that the lessons weren’t simply task-based lessons implemented willy-nilly. I also feel that the assessment criteria (which is showed to learners and made very clear) sets clear objectives for learners, and provides teachers with a good idea of what they should be providing feedback on. Some of the assessments are individual, and some are collaborative. We are still working through the details of these assessments (we’ve encountered some difficulties of course!).

Why on earth are we doing this?

So, I can hear some of the more experienced TBLT practitioners saying, well all this sounds far too simple, and there really isn’t enough time. I hear you, and I understand the concerns from the uppercase TBLT practitioners, but we need to be realistic, and here I’d like to explore

- Time with learners: The context is which I work is a private language academy in Spain, and our main type of ‘clients’ are Young Learners and Teens. We don’t have a lot of time with them, and the time that we do have with them needs to be focused on developing their language proficiency as well as preparing them for their exams. So, having these three lessons may put significant time pressure for teachers – any more than three and I imagine I’d be running up against negative teacher reactions, and this is something that we cannot have if we want this project to be a success.

- Teacher experience with TBLT: My teachers are not TBLT experts, but they have been experimenting with TBLT (mostly through the use of tasks from Anderson and McCutcheon’s Activities for Task-Based Learning). One of the goals of the project is to develop proficient TBLT practitioners through the use of a task-supported syllabus AND training, support, etc. (this will be touched on in another post). I also hope that by ensuring that teachers engage with the task sequences, there may be some spillover into their ‘normal’ (and I know that’s not the best word) classes; that is, I hope that as they become more experienced in using tasks, they start to use more tasks on their own.

Why is this posted under a ‘management’ theme

Some of you may be thinking “Why is this under Musings of An Academic Manager?”. There are a three main reasons:

- Implementing change in the Language Teaching Organisation (LTO): Any change within the LTO needs to have some kind of action plan, drivers of change need to be identified, objectives set, etc. The implementation of a task-supported syllabus is very much a management process then.

- Teachers don’t have time: I’ve often heard from managers that they want their teachers to use tasks and include more task-based teaching in their classes. While I can see the perspective on those managers, I also empathise and very much understand how teachers feel and how much time they have. In short, teachers don’t have a lot of time, and they certainly don’t have time to go away and create tasks that align with research. The onus, in my opinion, should be on managers to engage with research and TBLT theory, and then create tasks, either in the form of a task-supported syllabus or task-bank, for teachers.

In future posts, I will be going deeper into more of the management aspects of the project (e.g., teacher buy-in, feedback, budgets, etc.). I think for now, though, we’ve covered enough for one post 🙂

References

Long, M. (2015). Second Language Acquisition and Task-Based Language Teaching. Wiley Blackwell

I just want to say I hugely appreciate this post and adding more task-based lessons to courses is my school’s next big project.

LikeLike